Coronavirus: Is the pandemic finally coming to an end in India?

image copyrightReuters

image copyrightReutersIs the pandemic firmly in retreat in a country where many early modellers had predicted millions of deaths due to Covid-19?

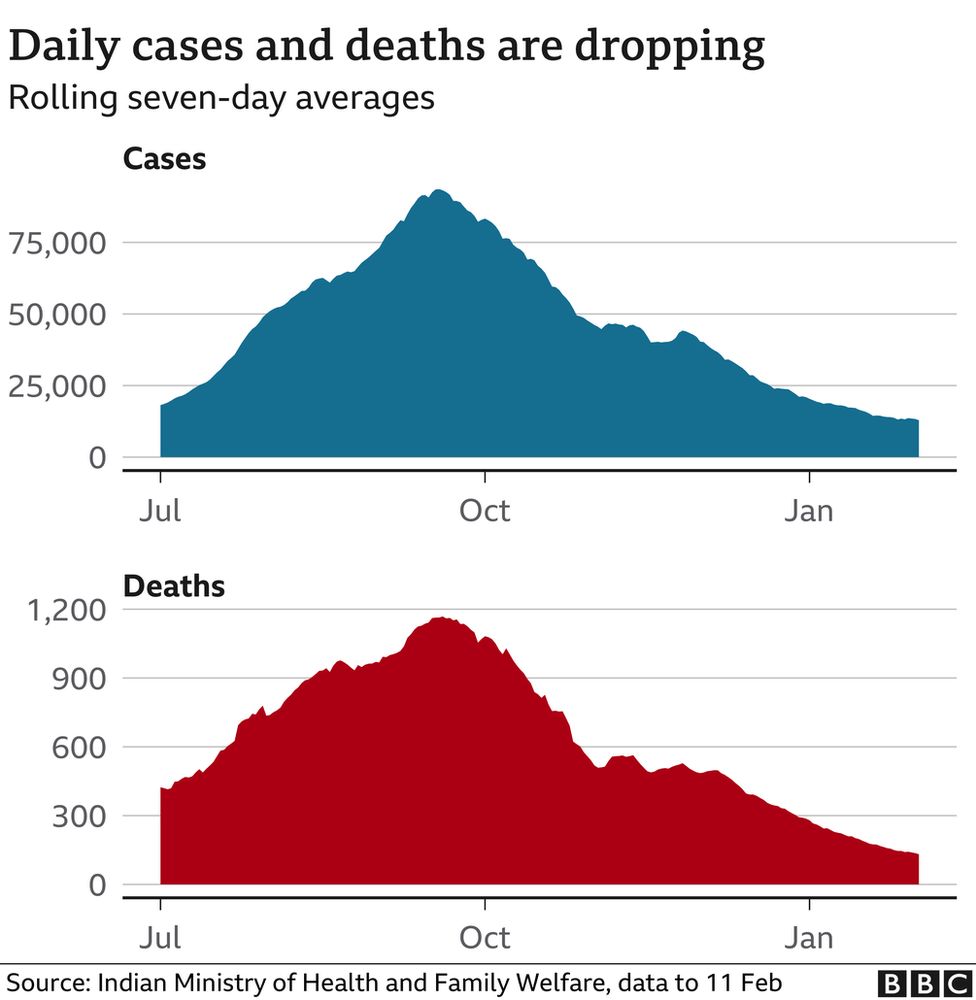

In October, I had written extensively on why the pandemic appeared to be slowing down in India. Cases had hit a record peak in the middle of September - there were more than a million active cases. After that daily deaths and caseloads began declining despite consistent testing and some short and fierce spikes of infections in cities like Delhi.

The situation has markedly improved since.

By the middle of last week, India was barely counting an average of 10,000 Covid cases every day. The seven-day rolling average of daily deaths from the disease slid to below 100. More than half of India's states were not reporting any Covid deaths. On Tuesday, Delhi, once an infection hotspot, did not record a single Covid death, for the first time in 10 months.

So far, India has recorded more than 10 million infections - the second-highest in the world after the US. There have been over 150,000 reported deaths from the disease. The number of deaths per million people stands at 112, much lower than what has been reported in Europe or North America. It is also clear that the decline in cases is not because of lower testing.

Most pandemics typically rise and fall in a bell-shaped curve. India has been no exception. Also, it has seen a high proportion of cases and deaths of people above the age of 65 living in densely packed cities, hewing to infection trends around the world.

"There's nothing unusual about infections dropping in India. There's no miracle here," says Dr Shahid Jameel, a leading virologist.

Experts say there's no dearth of possible causes - explained below - for the relatively low severity of the disease and its toll.

"We still don't have causal explanations. But we do know India as a nation is far from herd immunity," says Bhramar Mukherjee, a professor of biostatistics and epidemiology at the University of Michigan who has been closely tracking the pandemic. Herd immunity happens when a large portion of a community becomes immune to a disease through vaccination or through the mass spread of the disease.

Why is India far from reaching herd immunity?

The latest sero survey - studies that pick up antibodies - suggests 21% of adults and 25% of children have been already infected with the virus.

It also found that 31% of people living in slums, 26% of non-slum urban populations and 19% living in rural areas have been exposed to the virus. That's far below 50% - a figure reported by some of the bigger cities, such as Pune and Delhi. Here, there is evidence of much higher levels of exposure to the virus, hinting that these places are likely closer to herd immunity.

But experts say the numbers are still too low.

"There is no region in the country which can be deemed to have attained herd immunity, though small pockets may exist," Dr K Srinath Reddy, president of the Public Health Foundation of India, a Delhi-based think tank, told me.

So people who have still not been exposed to the virus in places with high prevalence of infection may remain protected in their communities but would become vulnerable if they travelled to areas where transmission levels are lower.

So why are cases dropping?

Experts say there could be a couple of different reasons.

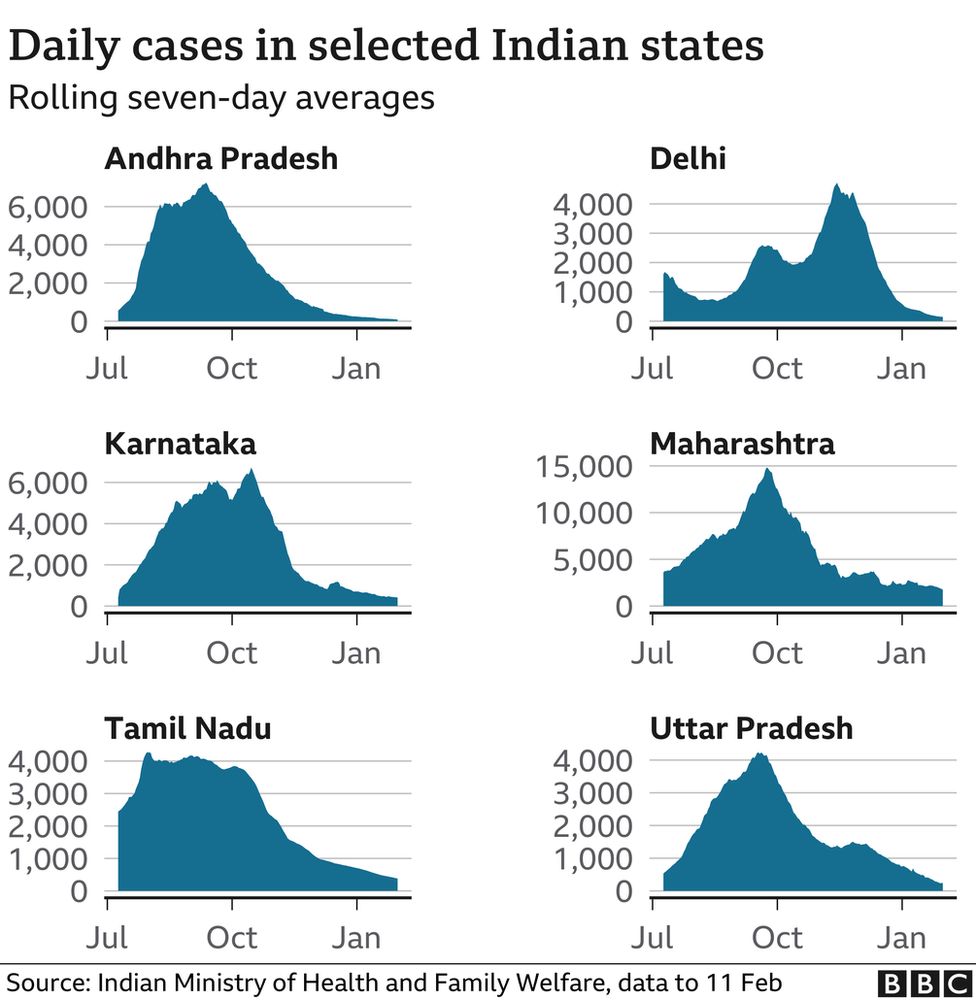

For one, India has seen a "patchwork" pandemic with cases waxing and waning at different times in different parts of the country.

More people have been infected in cities - especially in packed slums - and in developed, urbanised districts than in smaller towns or villages. In all of these places, their exposure to the virus has varied significantly. Cases have now slowed down in most urban areas, but rural India still remains a bit of a mystery.

"My hunch is exposure to the infection is much higher than what the surveys indicate. Also we should not be taking India as one. In some cities like Delhi, Mumbai, Pune, and Bangalore, up to 60% of people have been found with antibodies to the virus. So it's all very uneven," says Dr Shahid Jameel, a leading virologist.

The other explanation is that India has and continues to miss lots of cases, mainly because a large number of infected people have no symptoms at all or have a very mild infection.

"If we have had a massive number of very mild or asymptomatic cases, we might have reached a threshold of herd immunity already. If that is the case we still have to explain, why so many Indian cases have been so mild?" asks Partha Mukhopadhyay, a senior fellow at Delhi's Centre for Policy Research, who has been studying the pandemic.

Is the low death rate a mystery?

Most scientists believe that many more Indians died of the infection than what the official figures reveal. India has a poor record of certifying deaths and a large number of people die at home.

But even such a scale of under-reporting has not caused public panic or overwhelmed hospitals. Consider this. India has some 600,000 villages. Even one undiagnosed and unreported death from Covid in each village every day would not overwhelm the public health system.

India imposed a sweeping, early shutdown in late March to halt the spread of the virus. Scientists believe that the shutdown, which stretched to nearly 70 days, did prevent a lot of infections and deaths.

Transmission slowed in the badly-hit cities because of the expanded use of face masks, physical distancing, school and office closures and people working from home.

Scientists have also attributed lower fatalities to a young population, protective immunity, a vast rural populace with negligible links with cities, genetics, poor hygiene, and ample lung protecting protein.

image copyrightReuters

image copyrightReutersA number of studies have said the infection is largely spread by the virus floating indoors, tiny droplets hanging in stagnant air in poorly ventilated rooms.

But more than 65% of Indians live and work in the countryside. Brazil, for example, is nearly three-times more urbanised than India, and that could partly explain the high number of cases and fatalities there, say scientists.

In cities, the overwhelming majority of India's workforce is engaged in the informal economy. This means many of them, such as construction workers or street vendors, do not work in closed spaces. "The transmission risks are lower for persons working in open or semi-closed ventilated spaces," Dr Reddy says.

Has India avoided a second wave?

It's too early to say.

Some experts fear that India could see a spurt in infections with the onset of the monsoons, which also marks the beginning of the country's influenza season. It lasts from June to September and wreaks flood havoc across South Asia every year.

"The beginning of the upcoming monsoon season is going to be critical. We can only make an informed assessment on whether the pandemic has truly run its course in India after the season is over, " says an epidemiologist who preferred to be unnamed.

The real elephants in the room, say scientists, are the new variants of the virus identified in South Africa, Brazil and the UK.

Since a large number of Indians have still not been exposed to Covid-19, a dominant strain could easily travel to relatively uninfected areas and trigger fresh outbreaks.

India had reported more than 160 cases of the UK variant until the end of January. It's not clear whether the other variants are already circulating in the country. India could also easily have home-grown variants.

image copyrightReuters

image copyrightReutersThe UK variant was detected in Kent in September, but became the reason for a full-blown second wave only two months later. Since then it has been found in more than 50 countries, and is now set to become the world's dominant strain.

India has enough scientific labs, but genome sequencing is still spotty, scientists say.

"The variant story is the big one. It could upset all our calculations. We need to be very vigilant, and our labs should scale up genome sequencing to look out for variants," Dr Jameel says.

Clearly, India needs to speed up its vaccination drive - some six million jabs have been given in just under a month. The government aims to inoculate 300 million people by August to make sure a second wave does not result in widespread infections.

And there's no room for complacency yet - doctors and scientists urge people to avoid mass gatherings and crowded areas, and continue to use face mask and practise hand hygiene.

No comments