Covid passports could deliver a 'summer of joy,' Denmark hopes

(CNN) — Like many countries around the world, Denmark is desperate to reopen the parts of its economy frozen by the pandemic.

The

kingdom of under six million people has become one of the most

efficient vaccination distributors in Europe and aims to have offered

its whole population a jab by June.

But

before that target is reached, there's pressure for life to get back to

normal for Danes already inoculated and to open up borders for

Covid-immune travelers from overseas.

Morten

Bødskov, Denmark's acting finance minister, last week raised the

prospect of a so-called coronavirus passport being introduced by the end

of the month.

"Denmark

is still hard hit by the corona pandemic," he said. "But there are

parts of Danish society that need to move forward, and a business

community that needs to be able to travel."

The

government has since indicated that a February deadline might be

ambitious, but the relatively small Scandinavian country could still

become the world's first to formally embrace the technology to open its

borders in this controversial way.

'This is fundamental'

With

exports suffering and crucial business operations stuck in limbo,

Danish Foreign Minister Jeppe Kofod says the move is vital to keep

Denmark ahead of the game -- even if the country is under a lockdown

until February 28.

"We have more than 800,000 jobs in Denmark that are linked to trading with the world so this is fundamental" he tells CNN.

As

one of the world's most digitized countries, Denmark is ideally placed

to become a testing ground for this new technology, drawing on public

and private collaboration, says Kofod.

"This

is fundamental because if we want to start to export again and trading

again, see business people meet again, things like the corona passport

are fundamental to making that happen," he says.

Time running out

Denmark's business leaders want their country to blaze a trail with Covid passports.

Lars

Ramme Nielsen of Denmark's Chamber of Commerce also advocates for rapid

adoption of the technology, saying time is of the essence.

"If

we do nothing, if we sit and wait, nothing will happen," he told CNN.

"If you start when Covid-19 has left society, it will be too late. With

this project we're very positive we will have a summer of joy, of

football, of music. So better get started sooner, now, to plan."

Despite

the apparent imminence of this attempt to unlock its borders, Denmark

is currently living under its strictest Covid-19 lockdown to date amid

heightened concerns over the spread of the Kent strain of the virus

identified in the UK.

That

means anyone entering the country must produce a negative Covid test

and go into quarantine upon arrival. Restaurants, bars and hairdressers

are all closed with gatherings of more than five people banned.

The European soccer championships, which Denmark is scheduled to host this summer, feel like a very distant prospect.

So how will Denmark's Covid-19 "passport" work?

At

least four ready-made solutions exist based broadly on two types of

technology. One relies on remote cloud servers where information is

stored in bulk. The other uses blockchain, a more complicated system

that could be better at protecting privacy.

Since

personal medical data is so sensitive, it's a tricky decision. That's

why many European nations covered by stringent EU privacy laws appear

desperate for someone else to go first.

Digital toolbox

Denmark hopes to have a vaccine passport scheme in place by summer.

Ida Marie Odgaard/Ritzau Scanpix/AFP/Getty Images

The

high level of investment in developing Covid passport systems indicates

high private sector optimism that they will become a common way to open

borders.

The

International Air Transport Association has been working on one since

late 2020. Others with options ready to go include the nonprofit Commons

Project Foundation, computing giant IBM and secure ID company Clear.

Some

of these apps -- such as the Commons Project's cloud-designed

CommonPass -- are already being used in a limited manner by airlines.

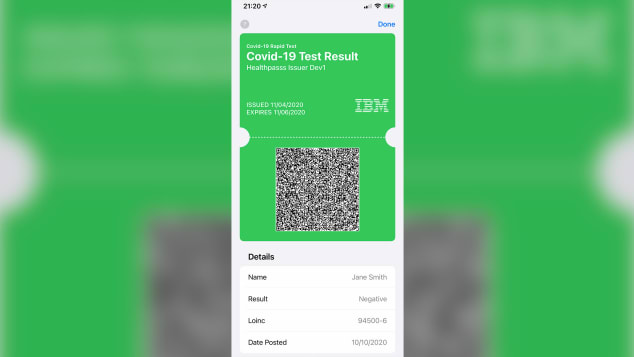

IBM,

which has had a worldwide team working on its "Digital Health Pass" for

nine months, uses QR codes that can be updated to reveal all sorts of

medical data that could be useful as the pandemic progresses.

"This

is a global initiative, and we have put this in a toolbox for any

government to use," says Carsten Storner of IBM Denmark. "It's not just

vaccines. We have opened it up to store all relevant data to Covid-19.

It's also your test results, your antigen test and who knows what the

future will entail in terms of variants."

Denmark's

planned passport would be rolled out first to business travelers, eager

to rekindle the commerce with foreign markets that accounts for a third

of its GDP.

Mette

Dobel, regional president of cement and mining firm FLSmidth, knows how

crucial it is for her staff to hit the road to open new markets and

maintain existing client relationships.

"We

are a business that cannot be driven through a web shop," she tells

CNN. "The face to face dialogue, especially on often relatively large

projects, is necessary. We have 300 people in Denmark who travel at all

times. We need to have our people travel."

Once

the business sector is up and running, the hope is that Denmark's

hospitality and mass entertainment sectors can then adopt the

coronavirus passport.

Dividing society

IBM's Digital Health Pass app creates an online vaccine credential that can be stored in a mobile wallet.

IBM

With a strong digital culture, Denmark could be the perfect testing ground for this new technology.

But

not everyone welcomes the concept, and there are fears it could create a

two-tier society that disadvantages the nonvaccinated.

New mother Chelina Hansen, who is eschewing a vaccine while she's nursing her infant, has lodged a petition on the Danish parliament's website to block the plans, with signatories saying the passports violate human rights.

"I'm against it because I am breastfeeding. I think the passport will

make it very hard for those who have not or do not want to have the

vaccine to navigate in society. I will split us into an A team and a B

team," she says.

Peder

Hvelplund, an elected official and health spokesman for the Red-Green

Alliance political group, asks why the country can't wait until everyone

is immunized in the summer, which is only a few months away.

"The

question is whether this makes sense at all," he says. "The more people

we vaccinate, the more the reproduction rate will drop. It is in the

interest of business to reopen for everyone, and allow as many people as

possible to take advantage of that."

Business leaders are divided on the subject.

Trade

bodies are lobbying hard for a passport scheme as soon as possible but

restaurateurs such as Philip Helgstrand, owner of the Restaurant

Strandhotellet in Dragoer, a port town south of Copenhagen, are unhappy.

Helgstrand

says it isn't feasible for small businesses to be responsible for

checking and handling each customer's Covid data, especially for

travelers from overseas such as the cruise ship passengers that once

made up a large share of his pre-pandemic customers.

"I

don't think it's fair to us to go and ask everybody who comes into the

restaurant," he says. "We already have to ask 'have you got a mask?

Don't sit too close to this and that.' It should be border control's job

and for the police to see the passport."

These arguments aren't unique to Denmark.

Last

year, advocacy group Privacy International warned vaccine rollouts

"must not be seen opportunistically as yet another data grab," warning

that "until everyone has access to an effective vaccine such passports

for entry of service will be unfair."

There are also concerns about how Covid passports could work globally.

After

botching the procurement and roll out of coronavirus vaccines, the EU's

next crisis could center upon how to standardize immunization records

to safeguard that most central of the bloc's principles: the Schengen

agreement on freedom of movement.

If

each country takes a different approach on whether to adopt a Covid-19

passport and chooses different systems, things could get messy quickly.

International project

Business officials say a Covid passport could allow Denmark to have a "summer of joy."

MICHAEL DROST-HANSEN/Ritzau Scanpix/AFP via Getty Images

How each member state views the subject seems to be affected by that state of its finances.

Greece,

which faced losing 70% of its tourism revenues last year, is reportedly

planning a Covid passport, as is Sweden. Hungary and Poland also both

have some form of digital immunity documentation in the works.

Europe's

most powerful countries, Germany and France, have not yet backed such

an initiative, despite similar laws already in place for other viral

diseases such as yellow fever.

In

a newly Brexited Britain, where more than 14 million people have

already had their first dose of a vaccine, the concept of a coronavirus

passport has received little support, although it is still being

debated.

Denmark

is aware part of its passport's success will lie in whether other

countries actually recognize it and not just inside the EU bloc.

"Of

course, it's important that there will be recognition of the passport

in other countries and that work has to ensure that now," says Kofod,

the Danish foreign minister.

Lars

Sandahl Sørensen of the Confederation Danish Industry sees room for the

UN and the WHO to get involved in some sort of certification process.

Without it, he says, Denmark will be cut off from what it needs to get

by.

"Denmark

is a nation that deals with and trades with the rest of the world," he

says. "We live off that interaction with the world, so this stops a

society like the Danish.

"We

want this to be an international project. We want to be able to

interact with other countries. But we start in Denmark to show this can

be done -- mobility in the country but also outside."

No comments