Egypt's revolution: I saw the unimaginable happen

image copyrightGetty Images

image copyrightGetty ImagesOn a quiet Tuesday, at the BBC Cairo office back in 2011, I was watching the aftermath of news coming from Tunisia.

It was just over a week since mass protests had forced the long-time, dictatorial President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali to flee his country, and like many Egyptians, I was wondering if this could set a precedent.

For three decades, we had been ruled with an iron fist by President Hosni Mubarak, nicknamed "the pharaoh" by ordinary Egyptians after the ancient, all-powerful monarchs.

Social media was abuzz with one sentence: "The answer is Tunisia." But somehow it was hard to believe such a thing could happen here.

It was 25 January, National Police Day, and there had been rare calls on Facebook for protests against police brutality and poor living standards. However, the authorities did not expect much of a response because strict emergency laws prohibited most mass gatherings.

image copyrightGetty Images

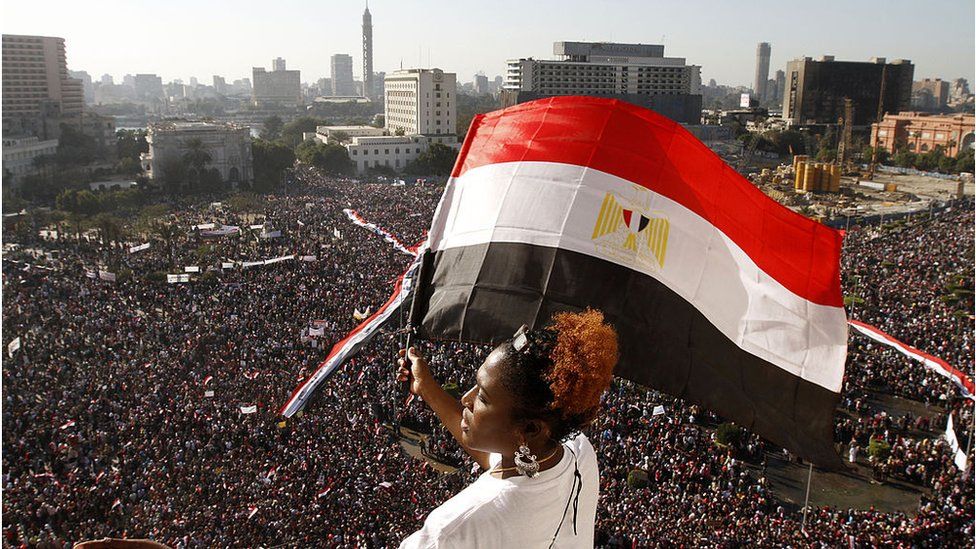

image copyrightGetty ImagesThen, suddenly, I heard reports that thousands of demonstrators demanding political and economic reforms had poured into the streets of Cairo. Immediately, I drove the short distance to Tahrir Square in the centre of the city and could not believe my eyes.

It was an extraordinary sight: young men and women from all walks of life crowding into the heart of the capital and chanting the same thing: "The people want the fall of the regime".

They were not from opposition parties or the Muslim Brotherhood, which was then Egypt's most organised Islamist group. Most were regular Egyptians who were bravely taking part in anti-government protests for the first time.

Daring to hope

During my life, I had known only Mubarak and his security apparatus. The shouts that I was hearing for democracy and freedom must have seemed to many like an unachievable dream.

And yet, the momentum only grew. By Friday, declared a "day of rage", protests had spread across the country. In total, I was to spend 18 days covering the popular uprising in Cairo and the coastal city of Alexandria.

I knew I was witnessing some historic moment. Behind the ups and downs - of dangerous clashes and defiance - for the first time in many people's lives a sense of change was in the air.

Each day brought incredible scenes: desperate young men staying put day and night - even daring to sleep on the metal tracks of army tanks - and others distributing free blankets and food to demonstrators, neatly repainting the kerbs and collecting rubbish.

image copyrightGetty Images

image copyrightGetty ImagesIn my interviews with protesters, it was clear they were determined, ready to sacrifice their lives for change.

When, finally, on 11 February, Mubarak stepped down, there was an outburst of joy and euphoria.

But it was not to last.

Short-lived solidarity

At first, power was handed to a military council, but then seeds of division were sown between former comrades in Tahrir Square: liberals and Islamists.

The first democratically elected president in Egypt was a Muslim Brotherhood leader, Mohammed Morsi. But in 2013, after just one year in power, he was ousted in popular protests supported by the armed forces.

The ugly stand-off that resulted with his supporters camping out for six weeks in Rabaa al-Adawiya Square was to end in a "massacre". Covering the bloody scenes was the lowest point in my career.

image copyrightGetty Images

image copyrightGetty ImagesIt is believed more than 900 people were killed in raids by the security services that described by Human Rights Watch as "crimes against humanity".

Later, in 2014, Egypt elected a new president - another military strongman - President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi.

Dashed dreams

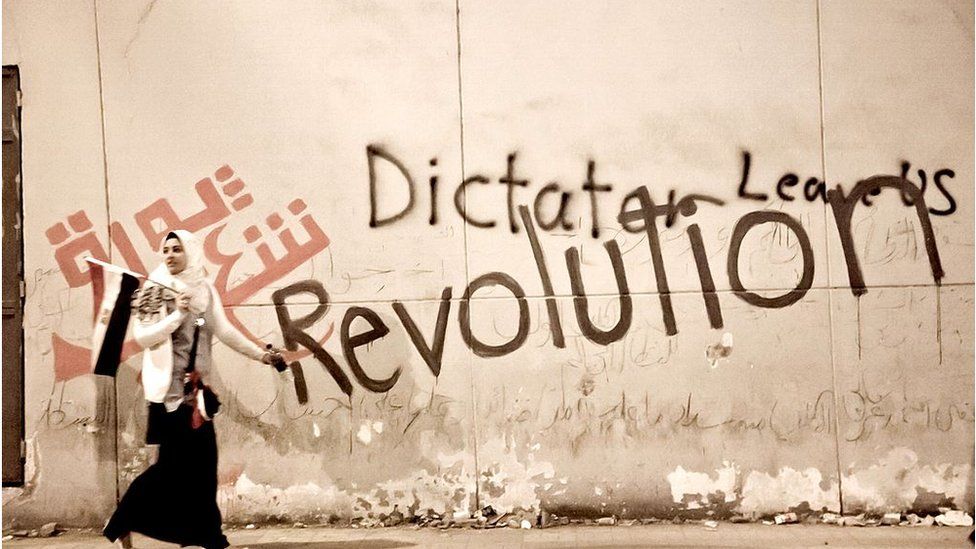

While many believed that the revolutionary spirit of Tahrir Square would always remain, President Sisi's government has since made strenuous efforts to dampen it.

Protesting has become more dangerous than ever: a way to get yourself shot or killed.

Ten years on from the day when many believed the revolution had achieved its goals, these have still not been met.

image copyrightAFP

image copyrightAFPInstead of freedom and social justice, the authorities systematically crack down on activists, bloggers, journalists and businessmen.

In April 2019, the Egyptian constitution was amended to pave the way for Mr Sisi to stay in power until 2030.

A few days ago, I drove home through Tahrir Square. Nowadays, it looks completely different and it is hard to imagine the seismic events that once unfolded there.

Nearby buildings have been repainted and there are bright, new lights. A new pharaonic obelisk, flanked by two rams, has been planted in the centre.

I considered stopping to take a picture but that is a risky business. Plain-clothed police dot the area.

On the 10th anniversary of the roaring Egyptian revolution, the square is silent with only traffic passing through.

No comments