The couples accused of destroying Japan's families

image copyrightMari Inoue

image copyrightMari InoueMari Inoue is a 34-year-old IT professor in Tokyo. She got engaged to her boyfriend Kotaro Usui three years ago. A wedding, they say, is out of the question.

It's not the pandemic that is preventing them, but an archaic Japanese law that requires married couples to adopt the same surname.

Theoretically either partner could give up their family name. In practice it is almost always the woman who loses hers: one study found it's them who change it 96% of the time.

"I find this very unfair," said Ms Inoue. "We should have the choice (to retain both)."

Her fiancé agrees. He considered becoming an Inoue but some relatives were unhappy. "I don't want to make any family sad," said Mr Usui. "We would like to be able to choose whether to change or keep one's name."

Japan is among only a few advanced economies to stop couples holding separate surnames after marriage - through a law that explicitly discriminates against women, according to a UN committee.

Six years ago two high-profile lawsuits aimed at changing the rules failed. But the movement for reform - joined by Ms Inoue and Mr Usui - has only grown.

An age-old battle

Surnames have long been contested territory.

In England a woman's desire to retain her maiden name was linked with unseemly "ambition" as early as 1605, wrote Dr Sophie Coulombeau.

Those who challenged the patriarchal practice met angry resistance, some eventually winning the right to use their names via landmark court cases starting in the late 1800s.

A similar battle was waged by suffragettes in the US. It took until 1972 for a string of legal judgments to confirm women could use their surnames however they liked.

More than 40 years later many in Japan were poised for their own watershed moment.

Kaori Oguni was one of the five plaintiffs who launched cases against the government, arguing that the law on surnames was unconstitutional and violated human rights.

But in 2015 Japan's Supreme Court decided it was reasonable to use one surname for a family, upholding the 19th Century rule.

"It felt like an arrogant teacher was scolding us," said Ms Oguni, still using her birth name informally. "I'd hoped the court would respect individual rights."

Instead the judge said it was parliament that should decide on whether to pass new legislation.

image copyrightTORU YAMANAKA

image copyrightTORU YAMANAKAThe political sphere, like most workplaces in Japan, is dominated by men. Entrenched cultural expectations view childcare and housework as women's work even if they are employed outside the home. Sexism is rife.

Unsurprisingly then the country has a poor gender equality record, ranking 121st of 153 nations in the last World Economic Forum report.

The government says it wants more women to enter the shrinking workforce but the gender gap seems to be growing - Japan slipped 11 places from the previous equality study.

'A social death'

Since 2018, Naho Ida, a PR professional in Tokyo, has taken up the challenge of changing minds in parliament, lobbying MPs to back separate surnames through her campaign group Chinjyo Action.

For Naho, who prefers to go by her given name on second reference, the naming convention "feels like the proof of (women's) subordination".

Ida is in fact her ex-husband's name. When they married, in the 1990s, he told her he felt too ashamed to take her surname. Both her parents and his agreed the change was hers to bear. "I felt like I was invaded by my new surname," she said.

The 45-year-old has resigned herself to using Ida professionally, having published under it for decades, while remarriage has foisted on her a third unwanted legal surname.

image copyrightNaho Ida

image copyrightNaho Ida"Some people are happy (to change), but I feel it is a social death," she told the BBC.

Signs of change

The advent of Yoshihide Suga as Japan's new premier last year briefly raised hopes among activists like Naho, as he has openly backed surname reform.

But in December the government reneged on its goals for women's empowerment with a watered-down gender equality plan that omitted the surname issue.

It "may destroy the social structure based on family units", warned Sanae Takaichi, a former minister, at the time.

Just last week, Japan's newly appointed minister for women's empowerment and gender equality, Tamayo Marukawa, said she was opposed to a legal change allowing women to keep their birth name.

For many "a woman who doesn't want to take her husband's name disrupts much more than a nuclear family, she disrupts the whole idea of family", said Linda White, a professor in Japanese Studies at Middlebury College in the US.

She explained how Japan's traditional koseki (family registry) system, based on single-surname households, has helped preserve patriarchal control everywhere from government to big business.

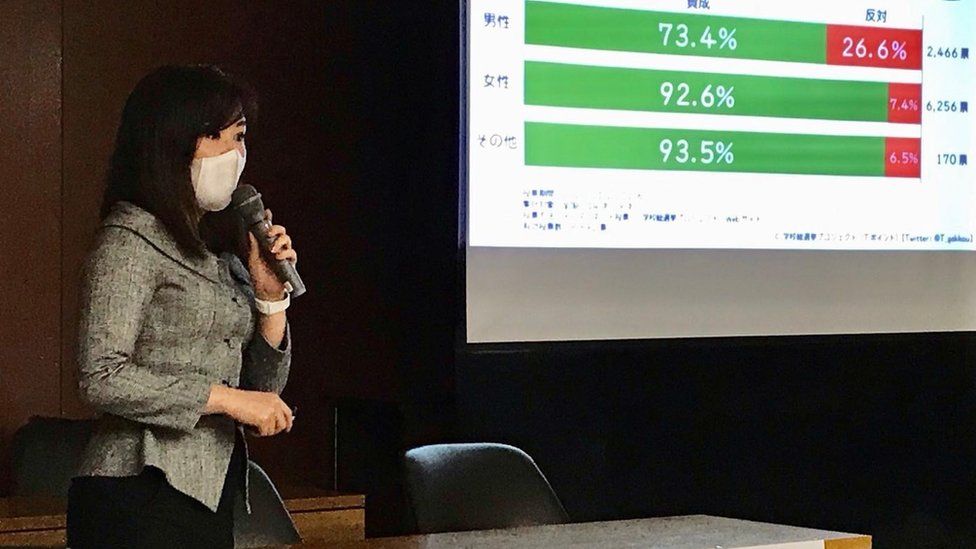

Japanese society itself seems open to change. Recent polls suggest a majority favour allowing married couples to keep separate surnames.

An October survey by Chinjyo Action and Waseda University showed that 71% supported giving people a choice.

image copyrightShuzo Saito

image copyrightShuzo SaitoIn this changing landscape nine new legal challenges are in progress. Unlike last time, when all but one of the plaintiffs were women, nearly every lawsuit involves a man too.

It appears to be a conscious strategy in a movement where many of the leading figures are framing the debate in terms of human rights rather than women's rights or feminism.

"It's more an individual identity and freedom issue" than a feminist one, said lead lawyer Fujiko Sakakibara, 67. "We wanted to show that it impacts men as much as women."

Of the 18 plaintiffs now locked in surname disputes, half are men. One is a prominent CEO of a Tokyo-based software firm who legally took his wife's surname upon marriage.

Another is Seiichi Yamasaki. The retired civil servant has been in a de-facto relationship with his partner for 28 years as they thought it was unfair for either to change names.

At the age of 71, Mr Yamasaki wants the next generation to have a choice while showing "there is demand among older people too".

In December three cases - including his - were referred to the grand bench of the Supreme Court, a move lawyers are viewing positively as it may indicate the court will make a fresh judgement on the surname rule this year.

"That male voice has made a big difference," reflected Naho, acknowledging the role of male allies in ending a patriarchal norm.

What's in a name anyway?

The fallout of a name change on a career is a big driver for many of the women advocating reform. The burden of changing names on dozens of official documents in paperwork-heavy Japan is another.

Those who opt not to marry because of the law also cite problems in situations such as hospital care where only legally married spouses can make decisions on each other's behalf.

What it ultimately comes down to for many women though is identity.

image copyrightAFP

image copyrightAFPIzumi Onji, an anaesthetist in the city of Hiroshima, took the unconventional step of divorcing her husband to get her name back. It's called a "paper divorce" in Japan as they are still living together decades later.

"That's me. That's my identity," says the 65-year-old plainly.

Dr Onji, who is also challenging the surname rule in court, knows she is one of a small minority who would actually use a revised law.

The overwhelming majority of Japanese women, like their counterparts in the UK and US, will still drop their surnames on marriage.

As Mihiko Sato (a pseudonym), a mother-of-two in her late 20s explained, adopting her husband's surname was a "natural" decision to feel "more united" as a family.

Many married British women might concur - almost 90% abandoned their names after getting wed, suggested a 2016 survey.

That the name change custom has persisted is a matter of surprise for some researchers in an era of greater gender consciousness and more women identifying as feminists.

Even those who don't, like many in Japan, say that tradition should not be used to stifle choice.

"Everyone should have the right to select their own surname," said Mrs Sato.

No comments