‘I feel like me again’ - troubled Army vets are helping fix driver shortage

Some UK veterans can face difficulties finding employment when returning to civilian life, but one ex-soldier wants to help them get back in the driving seat.

"Take your time, compose yourself, check your mirrors."

Darren Wright is training a new recruit to become an HGV driver. Many of the people that sit alongside him have something in common - they are all ex-military. The 46-year-old has been running Veterans into Logistics, a not-for-profit organisation in Greater Manchester, for 19 months.

"We get veterans who are struggling to find employment," he says. "We reach out to them, we put our [arms] around them and we support them into becoming HGV drivers."

Government figures published in 2017 show that of 952,000 veterans of working age, 28,000 were unemployed.

Darren says there is a lack of support for those who leave the armed forces without a trade or skill. Many he encounters are battling with low confidence or have mental health problems.

"They put a lot of trust in me," he says. "I can talk to them and go, 'Listen mate, I've been there, I know what it's like, but trust me, let's get you trained up, let's get you a job.'"

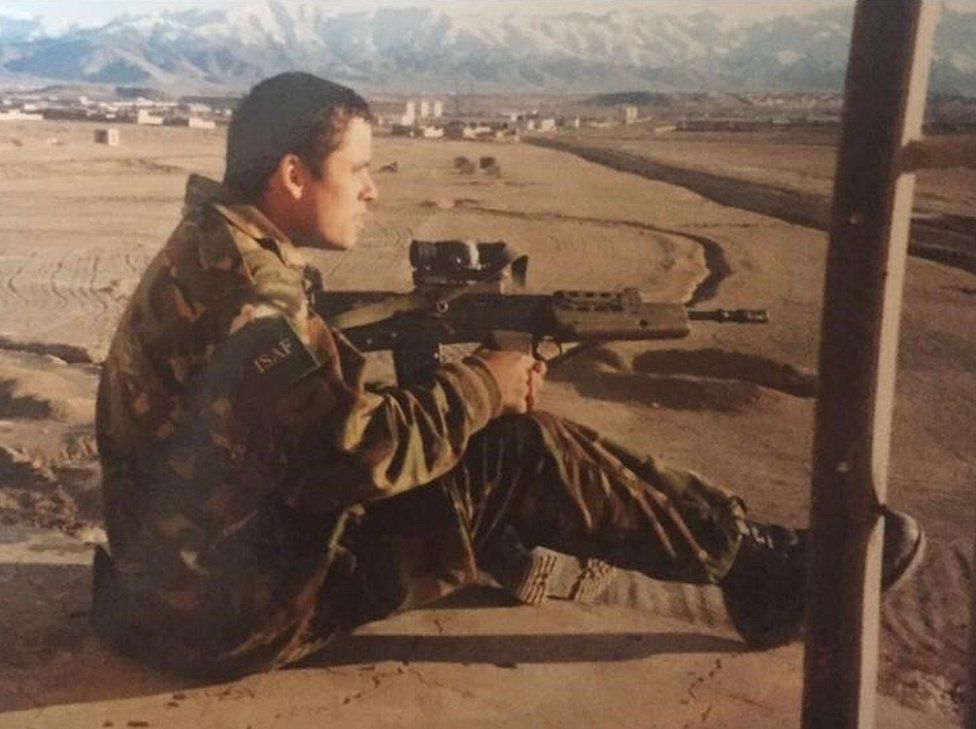

Growing up on a council estate in north Manchester, Darren left school without any qualifications or many prospects. He joined the Army at 23 and served as a gunner and paratrooper in 21 Battery, 47 Regiment, Royal Artillery for five years. He did a tour of Afghanistan and was discharged in 2004 suffering undiagnosed post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Image source, Darren Wright

Image source, Darren Wright

Find out more

- We Are England explores real stories from across England every Wednesday at 19:30 GMT on BBC One.

- Watch Veterans Road to Recovery on BBC iPlayer.

Returning to civilian life was difficult. "I was all over the place," he says "I was taking drugs and alcohol. I was in a bad way, a really bad way at the time. My marriage broke down. I became homeless. I was sofa surfing. I didn't want to be here."

He says his life spiralled even further out of control when he became involved in a gangland kidnapping in 2006.

- Watch We are England: Veterans Road to Recovery on BBC iPlayer.

- If you are affected by any of the issues raised in this story, support and advice is available via the BBC Action Line.

"Looking back to myself then, I wasn't well. I wasn't mentally right. Obviously I wouldn't do that now, and if I would have been a normal person, I wouldn't have done it then. My life was just a mess," says Darren.

"I regret the kidnap and the harm that it caused him and his family and I received over 11 years."

While in prison, Darren's PTSD was diagnosed and he received treatment, which changed his life. "I came out like me, I wanted to live, I wanted my life," he says.

He used his HGV licence, which he got in the Army, to earn an income and became a fuel tanker driver. It gave him structure, stability and financial security, as well as a purpose in life. Darren realised he wanted to do more to help other veterans after attending the funeral of a close friend who had taken his own life within a year of leaving the Army.

He sees his work as prevention. "Preventing someone from becoming homeless, preventing them from becoming suicidal, preventing them from ending up in prison," he says. "Why should a veteran be sleeping on the street, when they can get paid to sleep in a truck?"

He says ex-military personnel make good HGV drivers because they have discipline and are trained to think on their feet. Some already have experience of driving large vehicles in the forces. With an estimated shortage of more than 100,000 qualified HGV drivers in the UK and earnings of between £35,000-£50,000, getting an HGV licence can mean a job for life.

"The minute [Darren] handed me the sheet of how much you could earn my hands were shaking," says ex-soldier Daniel Birch, 35. "I thought, 'I've never earned that much money in my life.'"

Daniel joined the Army in his early 20s. He served four years in the 1st Battalion Irish Guards, which included performing ceremonial duties outside Buckingham Palace and St James's Palace. He also did a tour of Afghanistan, and still remembers how some of his comrades were injured by IEDs (Improvised Explosive Device).

"It really is like what you see in a film," says Daniel. "When it happened there's this moment's silence where you're taking it in, you can't believe what's gone on and the next minute you hear the screaming and you can't really put it in to words. It's a horrible scream, like a cry for help."

Overall, his transition back to civilian life went well. "The hardest part was finding a decent job. When I came out, the only job I could get was a healthcare assistant. I ended up in that job for three years but the wages were terrible. I was only on £11,000 a year on a zero hours contract."

Image source, Daniel Birch

Image source, Daniel BirchHe changed jobs twice, but things began to go downhill in 2017 when his dad was diagnosed with cancer. "That's when it started getting a bit hard mentally for me, because I was working, but then I'd be taking my dad to his treatments," he explains.

Daniel's partner Louise also gave birth to their youngest son, but health problems meant the baby had to stay in hospital for the first month of his life. He was later diagnosed with Worster-Drought syndrome, a disorder that affects the muscles around the throat and mouth. The couple's eldest son was also diagnosed with cerebral palsy.

"It just hit at once," says Daniel, "so I couldn't go to work and obviously if you can't go to work, you can't stay in a job. So I lost my job."

The couple became carers for their sons, relying on a carer's allowance. But being out of work affected his confidence. "It knocks your pride big time," he says. "I like working, earning my wage."

Four years later, when his sons started school, Daniel wanted to return to work. His partner had heard about Veterans into Logistics, and while he finds it difficult to ask for help, Daniel decided to send them an email. After passing the medical, theory and driving test in 2021, Daniel is now a qualified HGV driver and has a job working for a national dairy company.

"I feel like me again," he says, "because when I wasn't working, and with everything that went on, I think I lost myself and shut down."

Darren says it is "the best feeling" seeing the impact employment has on the veterans he trains. "At the beginning they're feeling down, they can't see an out, but once we support them and they're in jobs and they're earning a decent wage, they're just completely different people."

No comments