Climate change: What do scientists want from COP26 this week?

Image source, PA Media

Image source, PA MediaAs the COP26 climate summit enters its second week, negotiations in Glasgow have hit a critical phase.

The conference is seen as crucial if climate change is to be brought under control. So we asked more than a dozen climate scientists, negotiators and economists from around the world what they wanted to see agreed this week.

Cut emissions now

The scientists all wanted to see more countries commit to net zero by 2050 at the latest. Yet many said changes in the next decade would be the most impactful.

Governments must agree to "cut emissions by half in the next 10 years", says Prof Mark Maslin, who researches the impact of humans on the environment at University College London.

The Paris climate agreement in 2015 committed countries to reach net zero between 2050 and 2100. But reaching net zero is not easy and means big changes to transport, manufacturing, food supplies, construction and almost every aspect of life.

And many of the scientists think 2050 might be too late, particularly if countries don't cut emissions drastically before then.

"The longer you leave it, the more difficult it is to deliver net zero by 2050," says Prof Martin Siegert, who researches changes in glaciers at Imperial College London.

More than 100 countries have made the 2050 commitment, yet dozens have not. Others big emitters, such as China and Saudi Arabia, have made a net zero commitment - but by 2060, not 2050. One of the world's largest emitters, India, says it will get to net zero by 2070 - 20 years later.

The scientists said countries must sign up to go quicker. "We've got to get international consensus at least in principle around the notion of net zero by 2050," says Prof Siegert. "If that can be done at least in principle at Glasgow, it will be a major step forward."

The scientists we spoke to said investment in fossil fuels also had to be stopped, with money instead going into renewables like solar and wind.

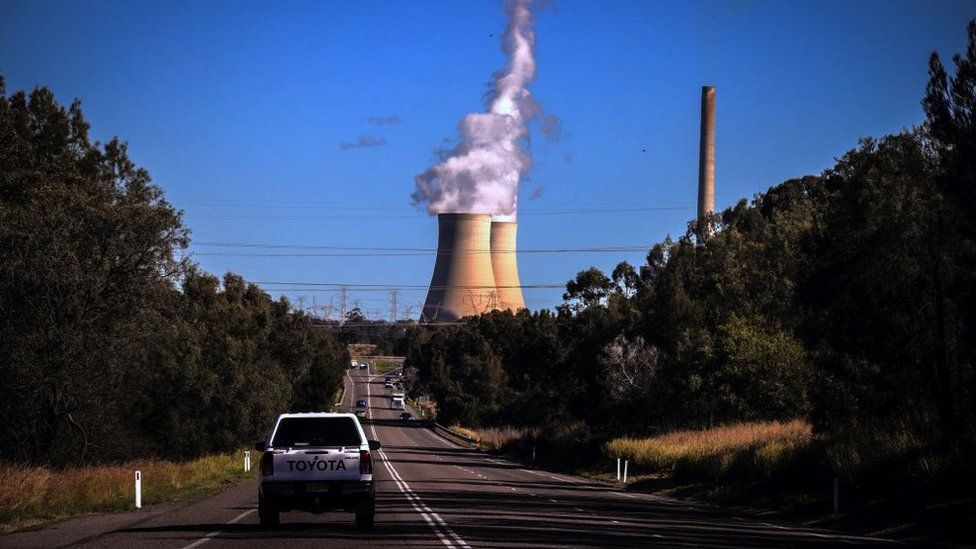

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty ImagesLast week at COP, there were announcements on cuts to coal and methane, but many scientists say they don't go far enough.

"There needs to be a blanket stop on any foreign investment that builds and supports coal power plants or any other fossil technology" says Prof Malte Meinhausen, of the University of Melbourne.

And Dr Natalie Jones, a specialist in existential risk at the University of Cambridge, says countries need to publish robust plans and policies on how they will achieve their targets.

Having plans on paper, or in law, makes it easier to get countries to stick to their word, she says. "It provides a kind of hook that you can use to hold countries accountable because you can say, 'well, you've promised this. This is your policy statement'."

"The UK, for example, has this relatively ambitious emissions reduction targets but it's concurrently trying to open a new oil field at the moment," she added. "The science tells us these things are fundamentally incompatible."

Make emissions more expensive

One proposal from the scientists was for every country to have a limit on how much it can emit.

However, what the limits for countries might be, and how any scheme might work in practice, is likely to lead to difficult negotiations. Previous attempts to reach an agreement have failed.

Image source, PA Media

Image source, PA MediaAn alternate solution, suggested by some we spoke to, was a global carbon tax system where consumers and companies, rather than governments, pay a tax on emissions.

By making business as usual more expensive, they argue, companies will be more likely to invest in cleaner technologies, which is essential to lowering emissions around the world.

"A carbon tax needs to happen," says Danae Kyriakopoulou a senior policy fellow at the London School of Economics. "We have to create incentives and create change in behaviour."

There is support for the idea. The head of the World Trade Organization recently called for a coordinated approach to taxes on emissions. However, higher costs could be passed on to consumers who use fossil fuels to drive their cars or heat their homes.

Ms Kyriakopoulou thinks this could be managed by taking the money raised by a tax and redirecting it to reduce costs. A country could subsidise home insulation to keep homes warmer and reduce the cost of bills, for example.

More money for poorer countries

Many people in developing countries, are suffering, says Dr Aditya Bahadur, a researcher at the International Institute for Environment and Development.

"They need resources to adapt to these changes. They need knowledge and information. They need new kinds of technologies. They need protective infrastructure."

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty ImagesThe developed world had pledged to provide $100bn a year to poorer countries by 2020, but this has slipped to 2023.

The US is already pledging more money, but the scientists we spoke to said reaching the commitment as soon as possible was important.

Dr Bahadur says a focus on adapting to climate change would allow countries to share technologies and advice on how to cope with extreme weather.

For example, a country that experiences droughts or floods frequently could give advice to others that have just started experiencing extreme weather events.

"I have a colleague in Bangladesh who says Bangladesh has a lot teach to Germany about how to deal with floods."

There is optimism for collaboration and knowledge-sharing among those we spoke to. The Covid-19 pandemic was given as an example for how countries can find ways to work together.

"I am optimistic that a lot of good things will come out of COP26," says Dr Nana Ama Browne Klutse, a scientist at the university of Ghana, in Accra. She contributed to a major UN report on climate change, published this year.

"Everyone wanted to fight this pandemic. The whole world kind of became one." She added: "This is how I want to see the fight against climate change. The world must come together to have this fight, with a common goal."

No comments