Ukraine crisis: The West fights back against Putin the disruptor

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty ImagesSuccessive US presidents have struggled to get the measure of Vladimir Putin but now that Brussels and Berlin have joined the fray with such resolve, it's a different story, writes Nick Bryant.

It is often tempting to look upon Vladimir Putin as the millennium bug in a human and deadly form.

The Russian president rose to power on 31 December 1999, as the world held its breath that computers would go into meltdown when the clock struck midnight, unable to process the change from 1999 to 2000.

In the 20 years since, Putin has been trying to engineer a different kind of global system malfunction, the destruction of the liberal international order. The former KGB spymaster wanted to turn back the clock: to revive Russia's tsarist greatness and to restore the might and menace of the Soviet Union prior to its break-up in 1991.

This Russian revanchist has become the most disruptive international leader of the 21st Century, the mastermind behind so much misery from Chechnya to Crimea, from Syria to the cathedral city of Salisbury. He has sought - successfully at times - to redraw the map of Europe.

He has tried - successfully at times - to immobilise the United Nations. He has been determined - successfully at times - to weaken America, and hasten its division and decline.

Putin came to power at a moment of western hubris. The United States was the sole superpower in a unipolar world. Francis Fukuyama's End of History thesis, proclaiming the triumph of liberal democracy, was widely accepted.

Some economists even peddled the theory that recessions would be no more, partly because of the productivity gains of the new digital economy. It was also thought that globalisation, and the interdependence it wrought, would stop major economic powers fighting wars. The same utopianism attached itself to the internet, which was seen overwhelmingly as a force for global good.

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty ImagesIn the early days especially, the same misplaced optimism and wishful thinking coloured the west's approach to Putin - a figure, it is now obvious, who was trying to buck history and thwart democratisation, however many lives were lost in the process.

Successive US presidents have played into his hands. Bill Clinton, the occupant of the White House when Putin came to power, handed this ultra-nationalist a popular grievance by pushing for the expansion of Nato right up to Russia's borders. As George F Kennan, the famed architect of America's Cold War strategy of containment, warned at the time: "Expanding Nato would be the most fateful error of America policy in the entire post-Cold War era."

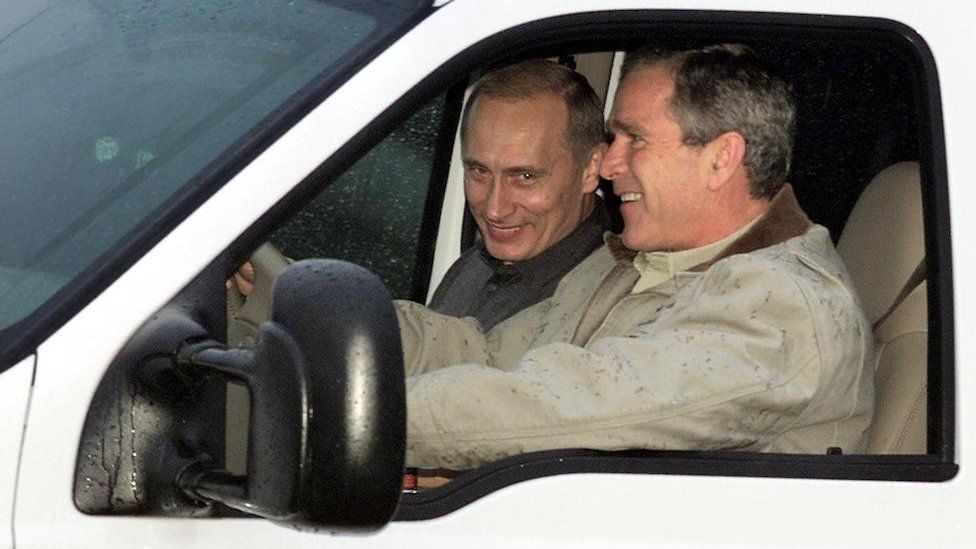

George W Bush completely misjudged his Russian counterpart. "I looked the man in the eye," Bush famously said after their first meeting in Slovenia in 2001. "I found him very straightforward and trustworthy… I was able to get a sense of his soul." Bush mistakenly thought he could mount a charm offensive with Putin, and gently cajole him further down the democratic path.

But even though Bush visited Russia more than any other country - including, as a personal favour, two trips in 2002 to Putin's home city, St Petersburg - the Russian leader was already displaying dangerously despotic tendencies.

In 2008, Bush's final year as president, Putin invaded Georgia - what he called a "peace enforcement operation". The Kremlin argued then - and has continued to argue ever since - that it was hypocritical for Washington to complain about this violation of international law after Bush had invaded Iraq.

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty ImagesBarack Obama sought to reframe US-Russian relations. His first secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, even handed her Russian counterpart Sergey Lavrov a mock reset button (which was mistakenly labelled with the Russian word for "overloaded"). But Putin knew that America, after its long wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, no longer wanted to police the world.

When Obama refused in 2013 to enforce his red-line warning against Bashar al-Assad when the Syrian dictator used chemical weapons against his own people, Putin saw a green light. By helping Assad carry out his murderous war, he extended Moscow's sphere of influence in the Middle East when the United States wanted to extract itself from the region. The following year, he annexed Crimea, and established a foothold in eastern Ukraine.

Despite being told by Obama to "cut it out," Putin even sought to influence the outcome of the 2016 presidential election in the hope that Hillary Clinton, a long-time nemesis, would be defeated and that Donald Trump, a long-time fan boy, would win.

The New York property tycoon made no secret of his admiration for Putin, a sycophantic approach that seems to have further emboldened the Russian president. Much to Moscow's delight, Trump publicly criticised Nato, weakened the US post-war alliance system and became such a polarising figure that he left America more politically divided than at any time since the Civil War.

More coverage of Ukraine crisis

- THE BASICS: Why is Putin invading Ukraine?

- TACTICS: Russia meets resistance with more firepower

- OLIGARCHS: The mega-rich men facing global sanctions

- IN DEPTH: Full coverage of the conflict

Arguably, then, you have to reach back 30 years to find a US leader whose approach to the Kremlin has stood the test of time. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, George Herbert Walker Bush resisted the temptation to rejoice in America's Cold War victory - much to the astonishment of the White House press pack, he refused to travel to Berlin for a victory lap - knowing that it would bolster hardliners in the Politburo and military seeking to oust Mikhail Gorbachev.

That magnanimity in victory helped when it came to bringing about the reunification of Germany, which was arguably Bush's greatest foreign policy success.

Putin is obviously a more formidable adversary, harder to deal with than even Leonid Brezhnev or Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet premier during the Cuban Missile Crisis. But since the turn of the century no US president has truly had his measure.

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty ImagesJoe Biden, like George Herbert Walker Bush, is a Cold War warrior, who has dedicated his presidency to defending democracy at home and abroad. Seeking to re-establish America's traditional post-war role as the leader of the free world, he has sought to mobilise the international community, offered military aid to Ukraine and adopted the toughest sanction regime ever targeted against Putin.

As Russian forces amassed at the border, he also shared US intelligence showing that Putin had decided to invade, in ways that sought to disrupt the Kremlin's usual misinformation campaigns and false flag operations.

His State of the Union address became a rallying cry. "Freedom will always triumph over tyranny," he said. And while Biden does not the speak with the clarity or force of a Kennedy or a Reagan, it was nonetheless a significant speech.

What's been striking since the Russian invasion started, however, has been the assertion of forceful presidential leadership from elsewhere. Volodymyr Zelensky has been lauded and lionised, as he has continued this extraordinary personal journey from comedian to Churchillian colossus.

In Brussels, the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, has been another commanding presence. This former German politician has been a driving force behind the decision, for the first time in EU history, to finance and purchase weapons for a nation under attack, a commitment that includes not just ammunition but fighter jets as well.

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty ImagesHer compatriot, the new Chancellor of Germany Olaf Scholz, has also shown more resolve in dealing with Putin than his predecessor Angela Merkel. At warp speed, he has overturned decades of post-Cold War German foreign policy, an approach so often predicated on caution and timidity towards the Russian leader.

Berlin has sent anti-tank and anti-aircraft systems to Ukraine (ending the policy of not sending weapons to active war zones), halted the Nord Stream 2 Baltic Sea gas pipeline project, withdrawn its opposition to blocking Russia from the SWIFT international payments system, and even committed to spending 2% of its GDP on defence spending.

The biggest assault on a European state since World War Two has stiffened European resolve. But so, too, it seems has the relative weakness of America. Mindful of the botched US withdrawal from Afghanistan and possibility of a Trump 2.0 presidency, European leaders seem to have realised that they can no longer lean so heavily on Washington to defend democracy in this hour of maximum peril. Leadership of the free world has, in this crisis, become a common endeavour.

Even since the end of the Cold War, Washington has been calling upon European nations to do more to police its own neighbourhood, something they failed to do when the break-up of the former Yugoslavia sparked the Bosnian war. Historians may well conclude that it took a combination of Putin's aggressiveness, America's fragility, Ukraine's heroic resolve and the fear that Europe's post-war stability is truly on the line to finally make that happen.

It would be naive to be swept away by the romanticism of Zelensky's speeches or to succumb to the dopamine high of watching the seizure of Russian-owned super-yachts unfold on social media. Putin is intensifying the war. But the last week has sent a message to Moscow - and to Beijing as well - that the post-war international order still continues to function, despite the deployment of the Russian war machine to bring about its collapse. Just as history never ended, nor has liberal democracy.

As Joe Biden put it in his State of the Union, during a passage in which rhetoric served also as sober analysis: Putin "thought he could roll into Ukraine and the world would roll over. Instead, he met a wall of resistance he never imagined".

Nick Bryant is the author of When America Stopped Being Great: a history of the present. He is the former New York correspondent for the BBC and now lives in Sydney.

No comments