Why China's climate policy matters to us all

China's carbon emissions are vast and growing, dwarfing those of other countries.

Experts agree that without big reductions in China's emissions, the world cannot win the fight against climate change.

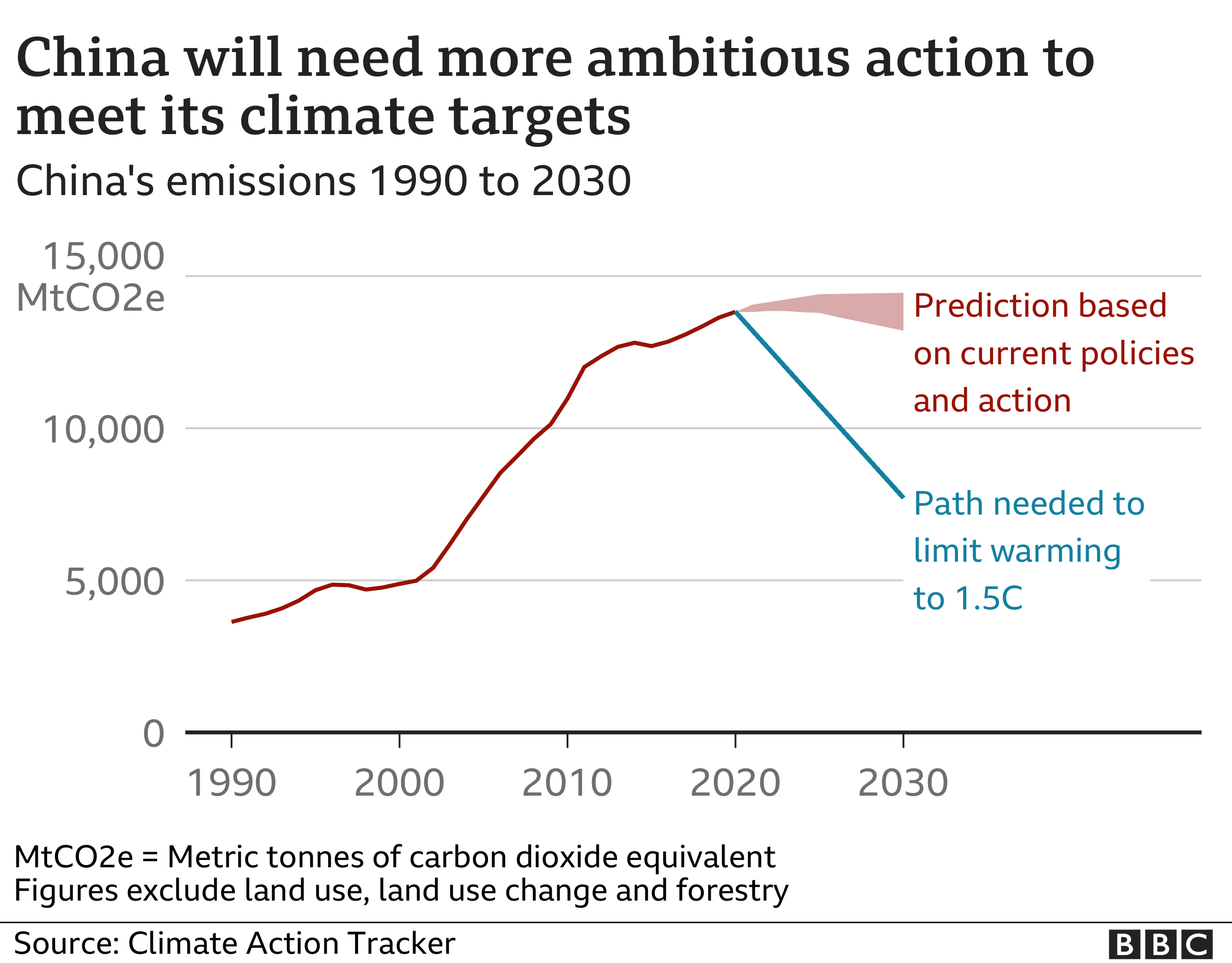

In 2020, China's President Xi Jinping said his country would aim for its emissions to reach their highest point before 2030 and for carbon neutrality before 2060.

His statement has now been confirmed as China's official position ahead of the COP26 global climate summit in Glasgow.

But China has not said exactly how these goals will be achieved.

Explosive growth

While all countries face problems getting their emissions down, China is facing the biggest challenge.

Per person, China's emissions are about half those of the US, but its huge 1.4 billion population and explosive economic growth have pushed it way ahead of any other country in its overall emissions.

China became the world's largest emitter of carbon dioxide in 2006 and is now responsible for more than a quarter of the world's overall greenhouse gas emissions.

It is expected to come under intense scrutiny at the COP26 summit over its commitments to reduce these.

Along with all the other signatories to the Paris Agreement in 2015, China agreed to make changes to try to keep global warming at 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, and "well below" 2C.

China strengthened its commitments in 2020, but Climate Action Tracker, an international group of scientists and policy experts say its current actions to meet that goal are "highly insufficient".

Shift from coal

Getting China's emissions down is achievable, according to many experts, but will require a radical shift.

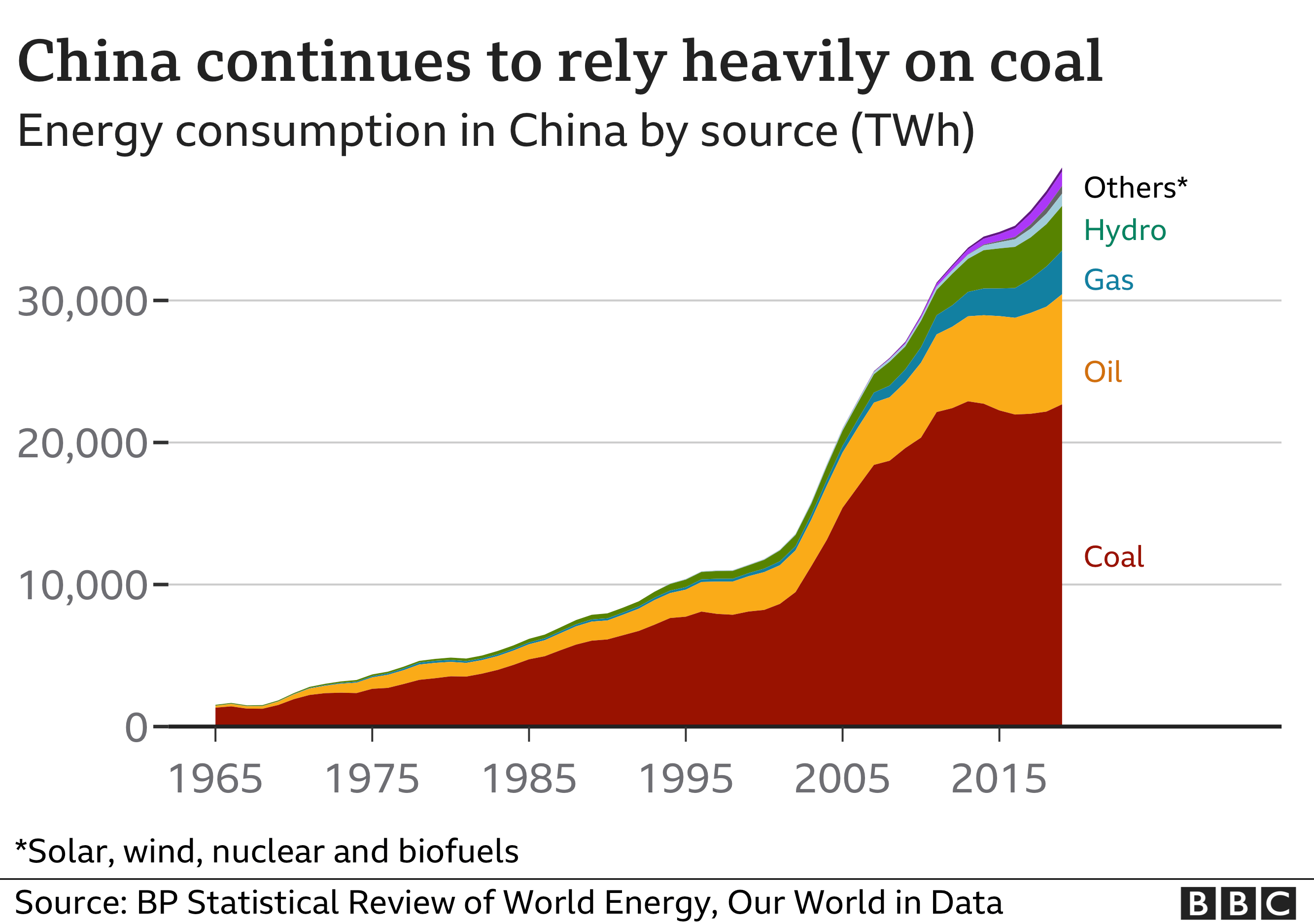

Coal has been the country's main source of energy for decades.

President Xi says China will "phase down" coal use from 2026 - and will not build new coal-fired projects abroad - but some governments and campaigners say the plans are not going far enough.

Researchers at Tsinghua University in Beijing say China will need to stop using coal entirely for generating electricity by 2050, to be replaced by nuclear and renewable energy production.

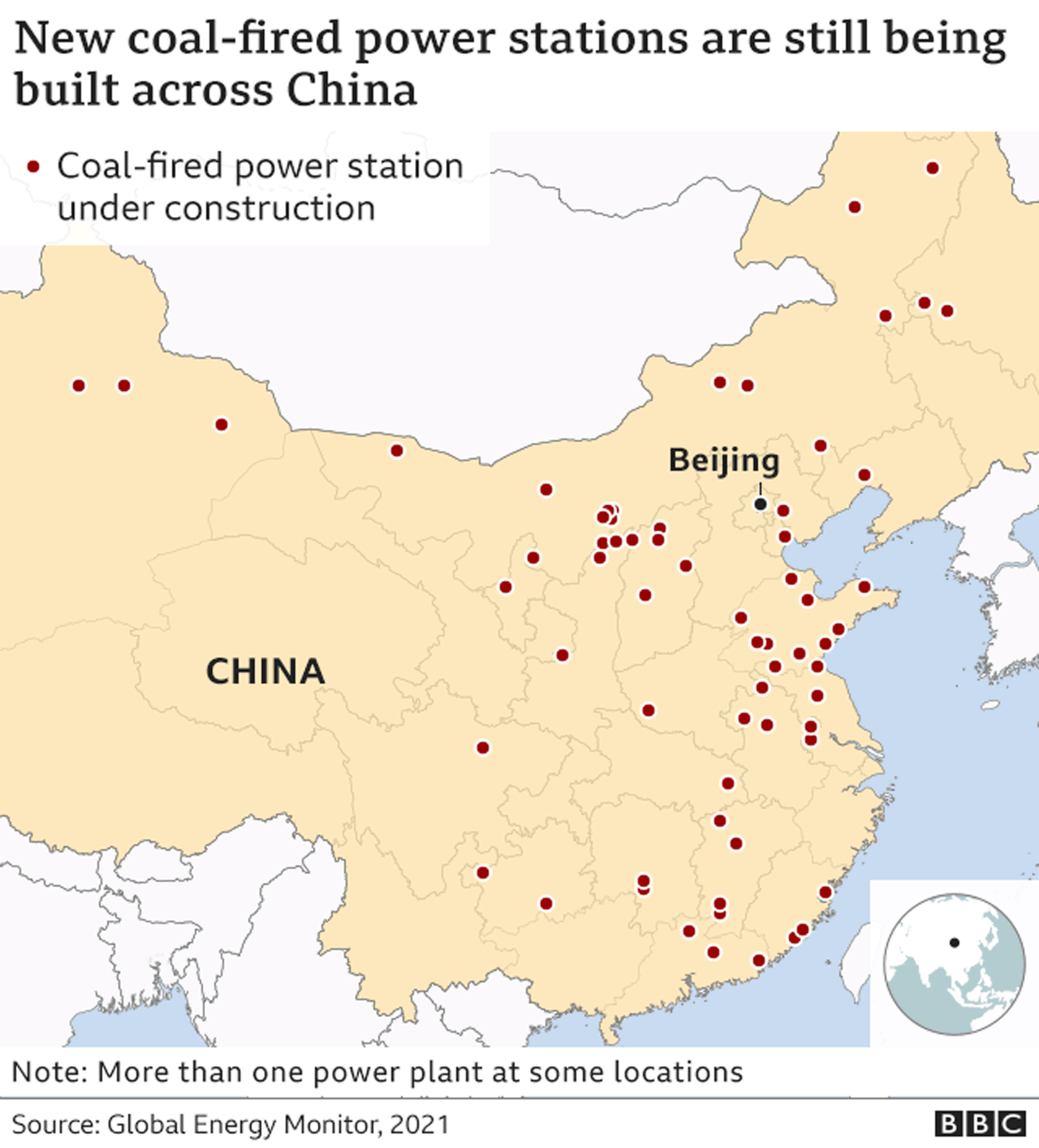

And far from shutting down coal-fired power stations, China is currently building new ones at more than 60 locations across the country, with many sites having more than one plant.

New stations are usually active for 30 to 40 years, so China will need to reduce the capacity of newer plants as well as close old ones if it is to bring emissions down, says researcher Philippe Ciais of the Institute of Environment and Climate Science in Paris.

It may be possible to retrofit some to capture emissions, but the technology to do so at scale is still developing, and many plants will have to be written off after minimal use.

China argues it has a right to do what Western countries have done in the past, releasing carbon dioxide in the process of developing its economy and reducing poverty.

In the short term, Beijing has ordered coal mines to increase production to avoid power shortages over the coming winter. Surging demand from heavy industry in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic has led to shortages in several regions of the country in recent weeks.

But China is switching to green energy

Tsinghua University researchers say 90% of power should come from nuclear and renewables by 2050.

In moving towards that goal, China's lead in the manufacture of green technology, such as solar panels and large-scale batteries, may be a big help.

China first embraced green technologies as a means to tackle air pollution, a serious problem for many cities.

But the government also believes they have enormous economic potential, providing jobs and income for millions of Chinese, as well as reducing China's dependence on foreign oil and gas.

"China is already leading the global energy transition," says Yue Cao of the Overseas Development Institute. "One of the reasons we are able to deploy cheaper and cheaper green technology is China."

China generates more solar power than any other country. That might not be so impressive given China's enormous population, but it is a sign of where the country is heading.

China's wind power installations were more than triple those of any other country in 2020.

China says the proportion of its energy generated from non-fossil fuel sources should be 25% by 2030, and it is expected by many observers to hit the target early.

Electric drive

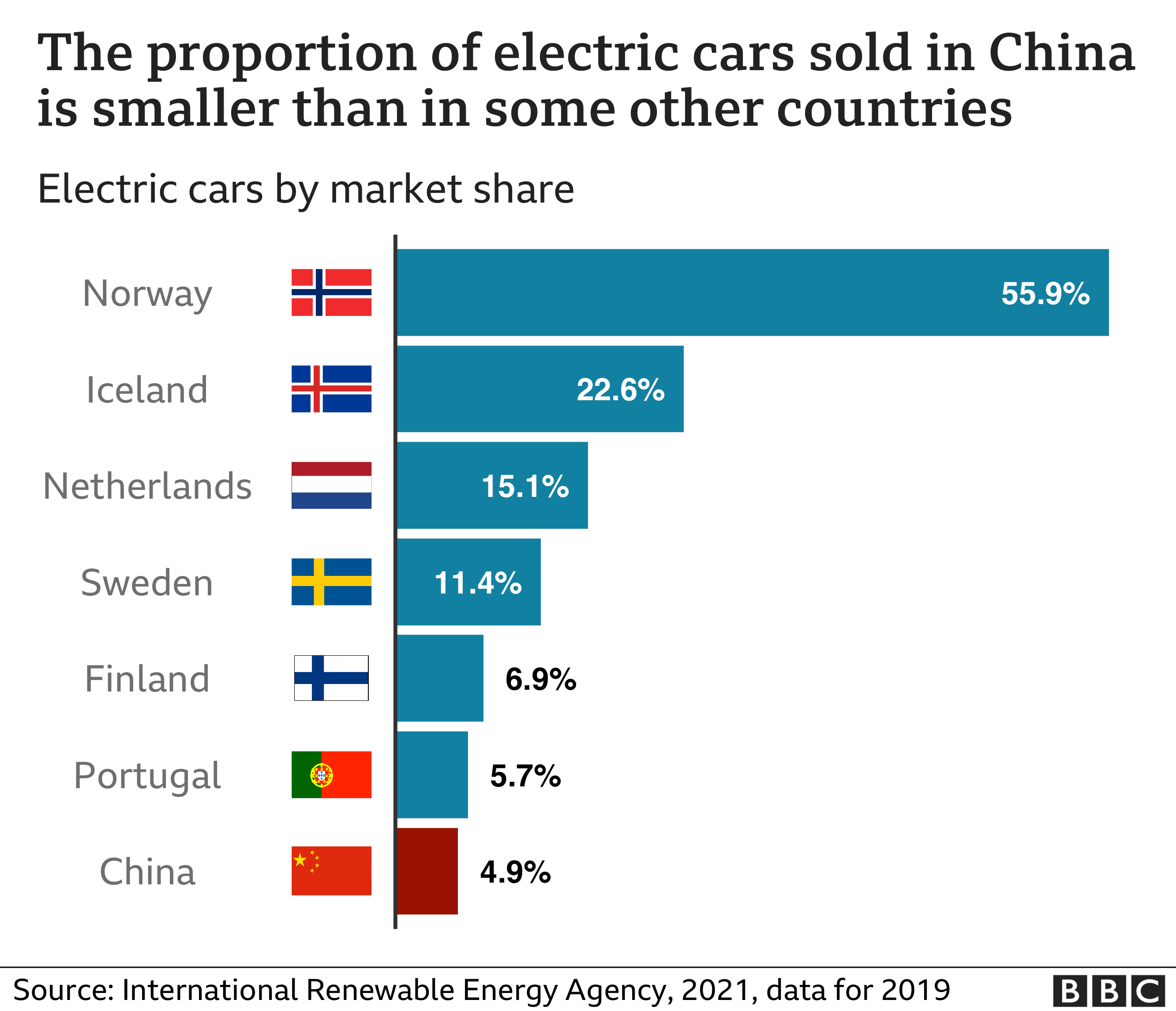

China ranks seventh in the world for its percentage of car sales that are electric, but given its huge size, China makes and buys more electric cars than any other country by a considerable margin.

Currently, about one in 20 cars bought in China is electric-powered.

By 2035, Chinese officials and car industry representatives are predicting that almost all new vehicles sold in China will be fully electric-powered or hybrid.

Working out by how much the shift to electric vehicles reduces emissions is not straightforward - particularly when taking into account manufacturing and charging sources.

But studies suggest that emissions over the lifetimes of electric vehicles are typically below those of petrol and diesel equivalents.

This matters because transport is responsible for around a quarter of carbon emissions from fuel combustion, with road vehicles being the largest emitters.

China will also by 2025 be producing batteries with double the capacity of those produced by the rest of the world combined.

Observers say that will enable the storage and release of energy from renewable sources on a previously impossible scale.

China's land is getting greener

Getting to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions doesn't mean that China will stop producing emissions.

It means China will cut emissions as much as possible and absorb what's left, through a combination of different approaches.

Increasing the area of land covered in vegetation will help, as plants absorb carbon dioxide.

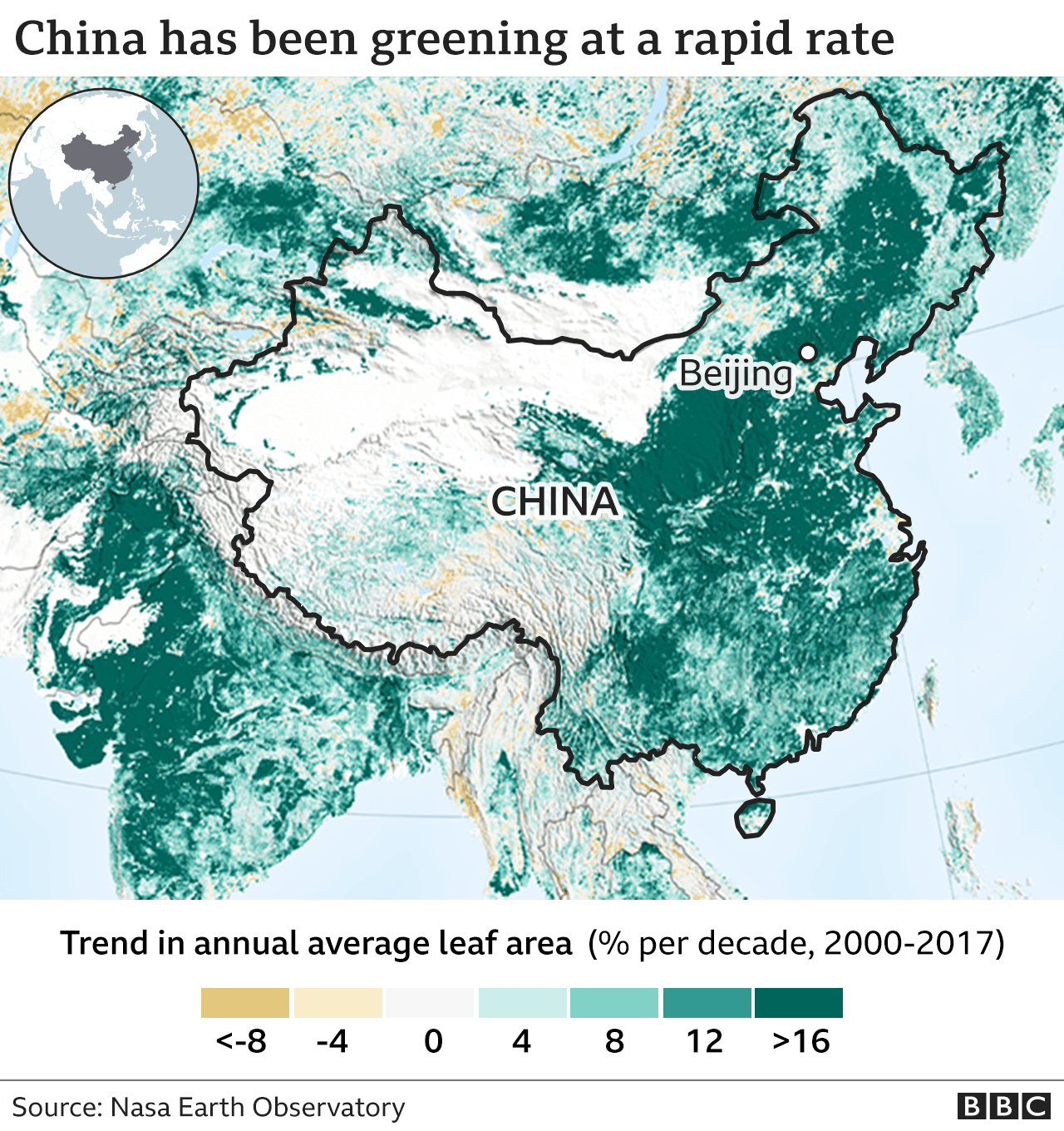

Here again, there is encouraging news. China is getting greener at a faster rate than any other country, largely as a result of its forestry programmes designed to reduce soil erosion and pollution.

It is also partly a result of replanting fields to produce more than one harvest per year, which keeps land covered in vegetation for longer.

What next?

The world needs China to succeed.

"Unless China decarbonises, we're not going to beat climate change," says prof David Tyfield of the Lancaster Environment Centre.

China has some big advantages, particularly its capacity to stick to long-term strategies and mobilise large-scale investments.

The Chinese authorities are facing a colossal task. What happens next could hardly be more important.

No comments